Reviewed and Approved by Shelly Blackwell, Sr. Dir. Dietary Supplements & Tobacco Consulting, EAS Consulting Group

1-Minute Summary

- The FDA continues to cite failure to verify component specifications as a top observation during inspections.

- Manufacturers must establish and document specifications for identity, purity, strength, composition, and potential contaminants.

- Identity testing must be performed on every lot of a dietary ingredient using appropriate methods; the manufacturer cannot rely on a supplier’s COA.

- The type of testing required depends on the nature of the component and the potential risks.

- Specification and Evaluation Forms help document compliance and should be controlled within the quality system.

Failure to Determine if Component Specifications Have Been Met

For more than a decade, the number one FDA observation for dietary supplement manufacturers has been consistent: failure to verify component specifications under 21 CFR 111.70 and 111.75.

In 2024 alone, the FDA issued 231 such observations. Clearly, this remains a common compliance issue.

This article outlines the regulatory requirements and explains the types of testing used to verify that dietary supplement specifications are met.

What Are Component Specifications, and Why Do They Matter?

Let’s start with a definition. Under 21 CFR 111.3, a component is any substance intended for use in the manufacture of a dietary supplement, including those that may not appear in the final batch of the dietary supplement. This includes dietary ingredients, excipients, flavorings, color additives, and processing aids.

According to 21 CFR 111.70(b), specifications must be established for each component in the following five categories:

- Identity

- Purity

- Strength

- Composition

- Potential contamination

What is a Component Specification?

Surprisingly, the FDA does not define the term “specification” in 21 CFR 111. Instead, we can look to the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Q6A: Guidance on Specifications – Test Procedures and Acceptance Criteria for New Drug Substances and New Drug Products: Chemical Substances.

It defines a specification as “A list of tests, references to analytical procedures, and appropriate acceptance criteria, which are numerical limits, ranges, or other criteria for the tests described.”

Identity: Is the Component Really What You Think It Is?

Identity is the most important specification in the FDA’s view. Under 21 CFR 111.75(a)(1)(i), manufacturers must test every dietary ingredient for identity prior to use. You may not rely on a supplier’s Certificate of Analysis (COA) for this test.

Your chosen method must unequivocally delineate the component from all others used at your facility. Vague results like “light brown powder” or “herbal odor” are not sufficient.

What Types of Tests Can I Use for Identity Testing?

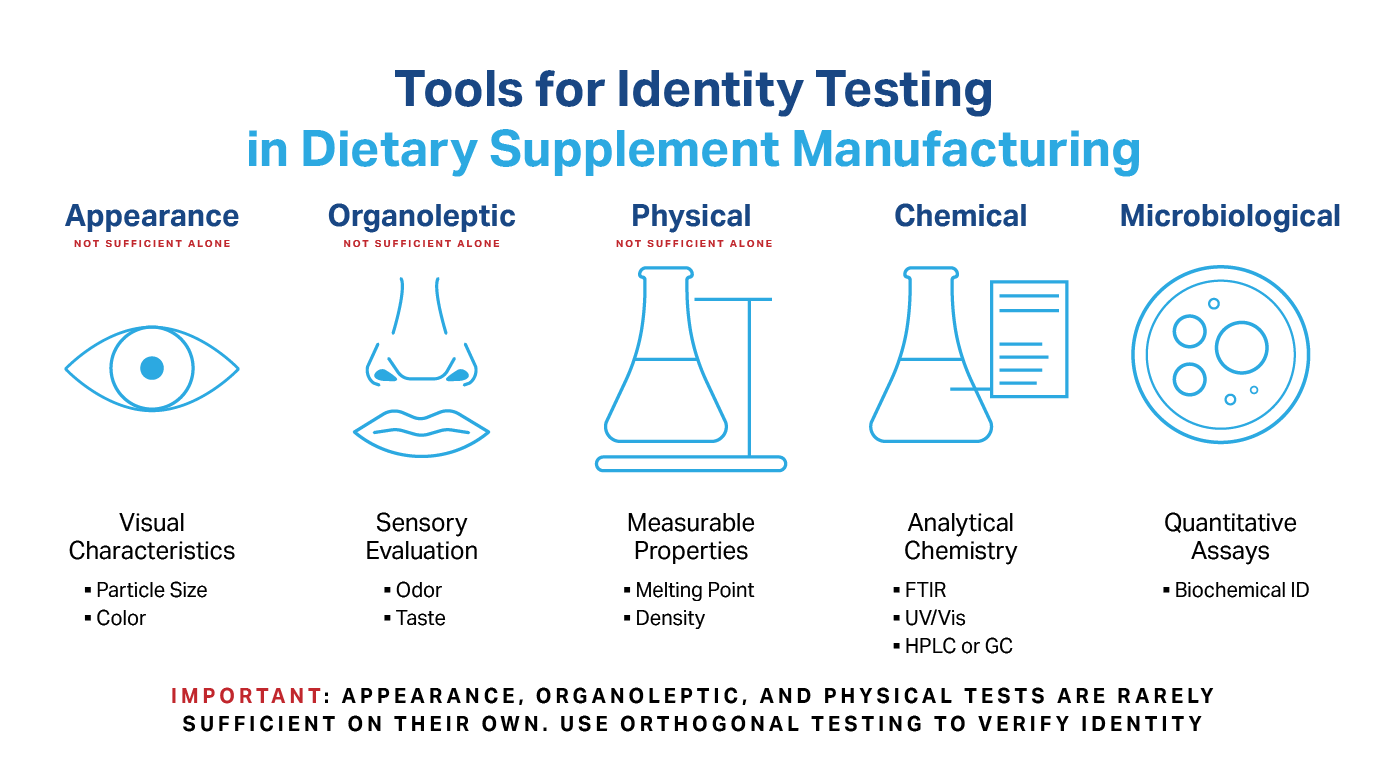

You have several options that fall into five general categories:

- Appearance – visual characteristics like particle type/size.

- Organoleptic – sensory attributes such as taste and odor.

- Physical – measurable properties like melting point or density.

- Chemical – methods such as chromatography or spectroscopy.

- Microbiological – quantitative assays.

It’s important to note that the first three on the list are rarely accepted alone since they often fail to “unequivocally delineate” the component from all other materials. Observing that the component’s appearance is, for example, a “light brown powder” is insufficient to meet this threshold.

Instead, a combination of tests, called “orthogonal testing”, may be required.

You may use wet chemical tests to identify minerals, salts, and chemical functional groups. You may also use analytical chemistry tests, which compare the analyte to a standard or reference material. These include…

- Ultraviolent and Visible Spectrometer (UV/VIS)

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry (FTIR)

- High-Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

- Chromatographic Methods (HPLC or GC)

If you need help understanding which method is right for your components, contact our dietary supplement testing labs and our experts can help.

Purity: Is the Component Free from Undesirable Matter?

“Purity” refers to the portion or percentage of a dietary supplement that represents the intended product.

Under 21 CFR 111, you must confirm component purity through testing before use in manufacturing. Purity testing can be divided into several subtypes, depending on the nature of the ingredient:

- Foreign Matter – Visual or microscopic examination.

- Chromatographic Purity – Detects related compounds or degradation products.

- Microbiological Purity – Ensures absence of bioburden or pathogens.

Microbiological Purity: The Most Common Focus of Purity Specifications

Purity testing most often refers to microbiological purity. This is especially true for plant-derived ingredients like powdered herbs, which are prone to microbial contamination due to their agricultural origin.

Microbiological purity is influenced by several factors:

- Material type – Botanicals, for example, often carry higher bioburden.

- Manufacturing processes – Wet granulation, for instance, increases water activity and risk of microbial growth.

- Intended consumer – Products marketed to infants, the elderly, or pregnant women may require stricter microbial limits.

Common microbiological tests include:

- Total Aerobic Plate Count

- Yeasts and Molds

- Bile-Tolerant Gram-Negative Bacteria

- Specific pathogens: E. coli, Salmonella, S. aureus, Listeria, Pseudomonas

Testing may be performed using traditional agar plate counts, Petrifilm, rapid test kits, or instrumental analyzers like automated microbial analyzers.

USP <2023> Microbiological Attributes of Nonsterile Nutritional and Dietary Supplements offers guidance on setting raw material microbiological specifications.

You can contact the experts at EAS Consulting Group, a Certified Group company, who have decades of experience working with companies to develop dietary supplement specifications.

Strength: How Much of the Ingredient Is Present?

Strength refers to the concentration of a dietary ingredient. This is a quantitative specification that must be confirmed prior to manufacturing.

Validated chemical tests are required to demonstrate that the analyte is present in the specified amount.

Which Methods Are Used for Strength Testing?

Here’s how that breaks down by category:

Vitamins and Other Ingredients

These analytes are typically tested using the following advanced chemical techniques that quantify the active component:

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

- Ultra High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC)

- Often equipped with detection systems such as:

- Ultraviolet and Visible Spectrometry (UV/VIS)

- Fluorescence

- Mass Spectrometry (MS)

- Triple quadrupole MS/MS

- Gas Chromatography (GC) – Used for volatile oil-soluble vitamins (e.g., Vitamin E)

- Detection via Flame Ionization Detection (FID) or MS/MS

Minerals

Minerals are quantified using either wet chemistry or more advanced instrumentation:

These methods are sensitive enough to detect minerals even at trace levels.

Botanicals

Botanical often require specialized techniques to detect marker compounds or bioactives.

- High-Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC) – Good for visualizing multiple constituents at once

- Chromatographic methods (HPLC or GC) – Used to quantify one or more chemical constituents or biomarkers

Composition: What’s Actually in the Material?

Composition refers to the overall makeup of a dietary ingredient, including its physical characteristics and the relative concentrations of its components.

Composition is especially relevant for complex mixtures such as botanical extracts, powders with multiple constituents, or finished products with several active and inactive ingredients.

What Does Composition Testing Involve?

Composition testing may be physical or chemical, depending on the product. Common examples include:

- Particle Size Analysis (PSA): Checks the size of powder or granules. For instance, a spec might say “at least 75% must pass through an 80-mesh screen.”

- Loss on Drying (LOD): Measures moisture to ensure the material stays stable and doesn’t support microbial growth.

- Relative Concentrations: Vitamins, sugars, polyphenols, etc.

- Organoleptic traits: Color, aroma, etc.

Contaminants: Is the Material Free from Unexpected or Harmful Substances?

Contaminants are unwanted substances that don’t belong in your product and may pose a risk to consumer safety, product quality, or regulatory compliance. They can be physical, chemical, or biological in nature, and their presence (or potential presence) should be accounted for in your component specifications.

According to 21 CFR 111.70(b)(3), you must establish specifications to limit contaminants “that may adulterate or may lead to adulteration” of the finished product.

What Counts as a Contaminant?

Contaminants vary depending on the source and type of material. Examples include:

- Physical contaminants – Metal fragments, glass, plastic shards, or other foreign objects introduced during harvesting or processing.

- Chemical contaminants – Pesticide residues, residual solvents, heavy metals, and adulterants such as melamine.

- Biological contaminants – Undeclared allergens, gluten, or contamination from other botanicals or animal-derived substances.

Examples of Contaminant Testing Based on Risk

The types of testing you require for contamination specification testing depends on your components, suppliers, target customers, and other variables. Common examples include:

- Botanicals and agricultural materials: Pesticide screening is often needed, especially for botanicals imported from regions with varied agricultural standards. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) are good sources of pesticide Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) for establishing your specifications. Test methods using HPLC/MS/MS, GC/MS, GC/MS/MS, GC/NPD, and GC/ECD are common.

- Extracts and materials made with solvents: If a botanical extract was processed using solvents like ethanol, hexane, or acetone, residual solvent testing is required. Testing is typically performed using GC/FID or GC/MS.

- Mineral-derived ingredients: These may carry heavy metals like arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury. ICP-MS or ICP-OES is typically used to quantify these contaminants.

- Protein-containing products: These are vulnerable to adulteration with melamine, a nitrogen-rich compound used to falsely boost apparent protein levels. Detection may require HPLC, GC/MS, GC/FID, or GC/NPD to produce accurate results below <2.5 ppm to conform to the FDA’s Guidance for Industry Pharmaceutical Components at Risk for Melamine Contamination.

- Allergen-sensitive or gluten-free products: ELISA allergen testing is common if your product is marketed as gluten-free.

Pulling It All Together: Specification and Evaluation Forms

Once you’ve established dietary supplement specifications for identity, purity, strength, composition, and contaminants, your next step is to document them clearly and evaluate incoming components against them. This is where Specification and Evaluation Forms come into play.

These forms should be managed like any other controlled document under your quality system. That means:

- Assigned document numbers and revision control.

- Reviewed and approved by the Quality Unit.

- Accessible to receiving, lab, and QA/QC personnel.

At a minimum, your specification form for a component should list:

- The component name and intended use.

- Each of the five required categories (identity, purity, strength, composition, contaminants).

- Test methods and acceptance criteria for each specification.

- Reference to compendial standards (e.g., USP, FCC, AOAC) when applicable.

- Any required documentation, such as a Certificate of Analysis (COA), vendor information, or prior qualification.

To view examples of Specification and Evaluation Forms, view our webinar: Dietary Component Specifications and Testing

Can You Rely on Supplier COAs?

Sometimes. You may rely on a supplier’s COA for strength, purity, composition, and contaminant specifications, but only if you’ve qualified the supplier and verified the accuracy of the CofA.

Qualification means you’ve assembled a package of evidence to demonstrate that the supplier:

- Has a consistent record of accurate test results.

- Uses validated methods.

- Is periodically audited or evaluated.

- Meets your internal quality standards.

However, you may not rely on a supplier COA for identity testing of dietary ingredients. As stated in 21 CFR 111.75(a)(1)(i), identity must always be verified independently, regardless of supplier status. If you use a contract lab for testing, be sure to perform an audit first.

Get Help Establishing and Testing Against Your Dietary Supplement Specifications

The FDA requires many tests for supplements in 21 CFR 111, in addition to the establishment of dietary supplement specifications. While it can be confusing, Certified Group companies are here to help.

Contact EAS Consulting Group if you need help establishing your specifications.